People have intense opinions about AI. Predictions about AI range from “it will replace 80% of jobs by 2030” to “it might automate just 5% of tasks this next decade if we’re lucky.”

Some propose that artificial general intelligence (AGI) may arrive in 2027, while “superforecasters” give AGI only a 1% chance of arriving by 2030.

Both extremes can’t be right, so how do we make sense of this? Let’s look at the spectrum of AI perspectives and why knowing where people sit can help us all make smarter choices.

Who’s Doing the Talking?

Not all AI predictions are created equal. Some come from scholars and researchers with decades of data to back it up, other guesses are from the social media comment section. Before we take an AI claim seriously, it’s worth asking who’s making it, and what’s in it for them.

Independent academics and investigative journalists are usually your safest bet. They tend to care more about accuracy than buzz, and they’re not trying to juice a stock price.

Frontier lab researchers live at the cutting edge, which means they’ve seen capabilities most of us haven’t — but that also means their optimism (or doom) can be amplified.

Engineers often focus on tools, not big-picture philosophy. They’re the ones who will tell you, “Yes, it’s neat, but here’s the bug list.”

VCs and big-tech CEOs? They’re in the business of selling visions — sometimes grand, sometimes grim, but almost always designed to keep you leaning forward in your seat.

Of course, no group is a monolith. You’ll find bold optimists in academia and staunch critics in boardrooms. That’s why we need a way to decode where each voice is coming from before we decide how much weight to give their forecast.

The AI Perspective Matrix

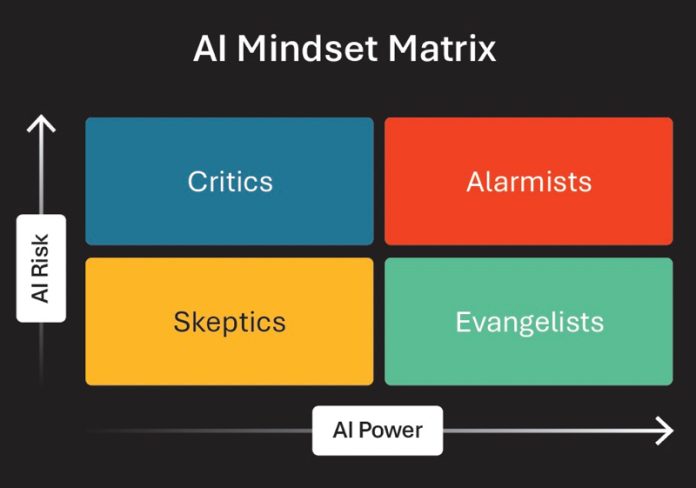

A matrix can be a good visual tool to navigate the chaos. On one axis: how powerful someone thinks AI will be (meh to life altering). On the other: how risky they believe it is (benign to catastrophic).

This gives us four distinct quadrants:

- Skeptics: AI is overhyped and

- Critics: AI is not that capable, but still

- Alarmists: AI is powerful and

- Evangelists: AI is powerful and amazing — let’s go!

- Disclaimer: These labels inevitably oversimplify. In reality, both risk and power are spectrums, and plenty of people live in the fuzzy edges between categories.

Real-World Voices On the Grid

When you start mapping the AI conversation onto the AI Mindset Matrix, certain voices light up their quadrant. Others are more difficult to place. But just as with any map, the terrain looks a lot clearer when you know who’s standing where and why.

In the Skeptics corner, you’ll find MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, who has become something of a patron saint for AI realists. He predicts that AI will automate only about 5% of tasks and give the global economy a modest 1% bump this decade. Hardly the revolution we’ve been promised.

Then there’s Anil Seth, a neuroscientist who’s spent his career studying consciousness. He’s quick to remind us that AI’s “thinking” is nothing like our own — and that claims of imminent sentience are, let’s say, generously optimistic.

Over in the Critics camp, the focus shifts from hype to harm. The industrial revolution-era Jevons Paradox makes a guest appearance here — the idea that greater efficiency can actually increase resource use. Applied to AI, it’s the fear that smarter systems could end up worsening our environmental footprint rather than shrinking it.

Benedetta Brevini, political economist and author of “Is AI Good for the Planet?,” takes that worry seriously, tracing AI’s impacts from mineral extraction to energy consumption. Sasha Luccioni at Hugging Face brings the receipts too, tracking emissions across the AI lifecycle and pushing for greener models. And stock analyst Peter Berezin adds a financial twist, arguing that if AI isn’t as powerful as advertised, its ROI may not justify the environmental or economic costs.

The throughline here is a sobering one: AI may be strong enough to create or deepen certain problems, but not strong enough to actually solve them.

Slide over to the Alarmists quadrant, and the stakes shoot up. Daniel Kokotajlo, a former OpenAI governance researcher, left the company over safety concerns and now warns of runaway AI progress in his “AI 2027” scenario. Tristan Harris, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology, paints a picture of AI that could warp attention spans, distort democracies and rewrite our value systems.

Author Yuval Noah Harari likens AI to an exceptionally capable but utterly unpredictable child, while AI researcher Yoshua Bengio insists we must keep AI as a non-agentic scientific tool — a safeguard against machines making their own catastrophic calls.

And then we have the Evangelists — the “full steam ahead” crowd. Demis Hassabis of DeepMind does present warnings of his own, but he also says it would be immoral not to pursue AI that could cure diseases or tackle climate change.

Big-tech CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, Sam Altman and Marc Benioff take turns pitching AI as the next great leap for humanity, whether it’s building digital social fabrics, colonizing Mars, ushering in AGI or scaling corporate empathy.

Meanwhile, David Sacks, the current White House AI Czar, frames AI as a competitive advantage for national growth, urging us to focus on winning the race rather than slowing it down.

Why this matters for the future of visual tech

Visual media has always been shaped by the tools we use, from the invention of film cameras to digital editing in Photoshop. AI is the latest (and maybe the most unpredictable) chapter in that story. Decisions about how we build, deploy and regulate visual AI aren’t happening in some far-off future. They’re happening right now, often under intense hype and uncertainty. Some

of us might be overestimating AI’s capabilities; others may be downplaying its risks. If we get this story wrong, we might end up betting our product roadmap, creative strategy or content policy on the wrong horse.

Making sense of AI isn’t about making the right prediction — it’s about appreciating the perspectives and biases behind who’s talking, why they believe what they do, and where they land in a spectrum of perspectives that each have their own basket of opportunities. Once you have that map, the noise starts sounding a lot more like a signal. In the technology sector, knowing who’s talking about AI and what incentives and biases they bring isn’t just useful context, it’s a competitive advantage.