Corporate leaders are asked to look forward and plan ahead, especially in times of great shifts such as the one we are experiencing. It is important, however, to look back, even to recent periods, and make sure that aspects of corporate culture you felt were important are not swept away with the tidal wave of change that is imminent in a post-pandemic world.

Take, for example, a prediction from Geoff Colvin, an author and longtime editor at Fortune magazine, in that publication’s January cover feature, “20 Ideas That Will Shape the 2020s.” “Showing up will matter again,” stated the headline on Colvin’s essay.

“In the 2020s, people in developed economies will rediscover the value of physical presence — engaging with others face-to-face, eye-to-eye. As the world has become more digital, the trend [toward social isolation] has accelerated.”

Colvin presented research that shows how damaging social isolation can be, significantly increasing the risk of heart disease and stroke. That knowledge, he argued, is fueling a countertrend of people wanting to be together. “Companies are encouraging or requiring employees to come back to the office because researchers find that creativity and innovation are group activities built on trust, and there is no substitute for face-to-face interaction to build up this trust.”

The demise of office culture

It’s hard to read Colvin’s prediction and realize it was published less than 90 days before the world went on lockdown, taking the idea of in-person collaboration with it. Much has been made of announcements by technology leaders such as Twitter and Facebook that work from home (now often referenced simply with the acronym WFH) is a permanent or semipermanent policy, at least for a substantial percentage of their work force. Media stories quoting corporate leaders indicate the WFH movement will be widespread.

“Peter Drucker said in the ’70s that office buildings would be like the Pyramids. We would come to marvel at them, but they would serve no functional purpose in the future. That was one of those interesting things that was ‘proven wrong,’ but he may be proven right,” says Scott Galloway, an author, entrepreneur, podcaster and professor of marketing at NYU’s Stern School of Business. “You might have the largest, most dramatic office buildings in the world converted to either condos or interesting museums.”

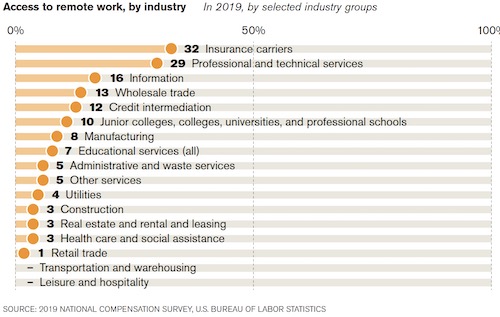

Offices won’t disappear anytime soon, but the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated many companies’ openness to permanently allowing at least part-time WFH policies. According to the 2019 National Compensation Survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 7% of civilian workers in the United States had access to a flexible workplace benefit, pre-pandemic. Workers who have access to it are largely managers and other white-collar “knowledge workers” who do most of their work on computers. Economists at the University of Chicago estimate that just 37% of U.S. jobs can be done remotely.

Nevertheless, a forecast on WFH from Global Workplace Analytics expects that those who were working remotely before the pandemic will increase their frequency long term. In addition, the report states, there will be a significant upswing in WFH adoption by those who did not work remotely until the pandemic. “Our best estimate is that we will see 25 to 30 percent of the workforce working at home on a multiple-days-a-week basis by the end of 2021,” says Global Workplace Analytics President Kate Lister.

Varied views

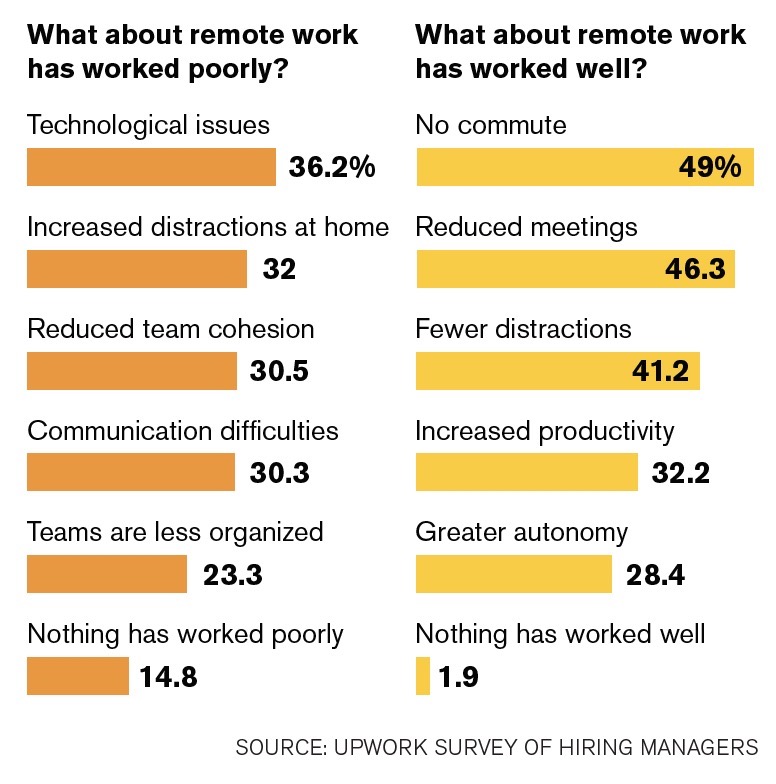

Employees tend to favor the option to work from home more than their managers, who often express a fear of less productivity, creativity and camaraderie. In a report on PBS NewsHour, David Kenny, CEO of Nielsen Holdings, says he was opposed to the company’s flexible work space policies when he arrived there at the beginning of 2019. In conferences that were a combination of in-person attendees and workers teleconferencing in, those who were not present in person were “largely not in the conversation,” Kenny says.

When Nielsen was forced to send its entire work force home to be safe during the pandemic, Kenny says it opened his eyes to the possibilities. “It’s been a big event in my life. I was forced to look at a total system change as opposed to an incremental change. I don’t think I would have had the courage to go big and have everyone try this if we weren’t forced to. It opened my eyes and showed me that with some things, if you do them big, they actually work.” For the long term, Kenny says most workers at Nielsen will be allowed to adopt a hybrid model, coming to the office only when it is necessary.

Other company leaders are less convinced. Scott Wine, the chief executive of Polaris Inc., the Minnesota-based manufacturer of snowmobile, motorcycles and other vehicles, told The Wall Street Journal that he expects his team will be back together for traditional work days when it’s safe.

“I do think there’s a hit on productivity from groups not being able to meet together spontaneously and solve problems,” Kenny told WSJ in May. “Most people haven’t been in the offices for two months now and they have embraced it, but it’s not something I want to keep in place forever.”

Working together is better

Colvin is in Kenny’s camp. He amassed a copious amount of research on the impact of isolated work for his 2015 book “Humans Are Underrated: What High Achievers Know That Brilliant Machines Never Will.” Many employers have defaulted to WFH out of necessity, but they should be careful with making that permanent, he says.

High-tech companies like Twitter and Facebook are mentioned as leaders in the WFH movement, yet Colvin says Apple, Google and other hyper-successful companies have always understood the power of physical presence and take extraordinary steps to bring employees together.

“Abundant research shows powerfully that people are more innovative, creative, effective and productive when they’re physically together,” Colvin states in an email to SMM. “They trust each other more. They are collectively smarter when physically together than when digitally together. It’s tempting to think that physical presence can’t possibly matter for some employees, such as call center workers. Not so. Even though they work entirely alone in individual cubicles, when call center workers are formed into teams with their breaks scheduled so they can all get together, their productivity rockets.”

Click on any of the articles below to read more from our “NEXT” special report.

Is working from home inevitable or overrated?

The office as a recruitment tool

Sales reps are ideally suited to work from home

Burnout becomes a bigger fear in WFH environments

Leaders must be mindful of the story behind the story